By dusk the wind freshened. We clipped along at seven knots in moderately choppy seas, the confused kind that prevails in the Malacca Strauit where traffic is heavy and water is shallow.

At 1930 Roo, on the wheel, sniffed the first of Denise’s perfume drifting into the cockpit, signaling her watch and a rest period for our mighty man Roo Biram.

Preparing to take the helm an exceptionally cheerful Denise brought a lengthy music play list. She tuned in Alabama and James Taylor to while away her shortened one hour watch, thinking, I’ll just pass my time and go back to bed.

“Wow Denise, you’re a cutie this noight” Roo said with authentic Australian twang. “She be a bit pitchy roight now and the winds hankerin to puff up. Best get your harness on there missy, before litin up the tunes.”

“Thanks Roo, help me with this stupid “D” ring. The captain always complains it’s important but my fingers aren’t strong enough to open and close the clip—but we gotta please the captain, right?”

“Roight-ee-oh,” Roo said. “I’ll clamp it fer you Missy, roight to the survival raft. You won’t be takin any trips in choppy seas that a-way, and I’ll jabber with the skipper about shortenin sail. Won’t be so hard for you then, drivin in this slop.”

Roo found me at the chart table. We called to Denise for instrument readings and checked repeater instruments below deck before agreeing to take a reef in the main.

“Could lose up to a knot, I suspect. Hey, who cares if we can make it comfortable. Denise will be pissed if a wave slurps over the side and she gets drenched.”

Roo took a small reef in Endymion’s roller furling. An advantage of slow sailing at night was not hitting floating obstacles or sailing into shallow spots where depth was a scant ten feet—not a safe margin for our six-foot keel.

Roo took his normal dozen humongous bites of whatever tucker (food) was available before announcing he was ‘a piker’ (quitter) and turning in until his next watch.

Don slept soundly in the salon leeward berth. I noticed he’d snapped in the canvas to prevent being tossed from his bunk should a freighter’s big wake roll us.

The ship’s clock struck one bell (2030 or 8:30). Denise said, “Ohhh—only a half hour left on my watch. Bless me.”

At the nav station I worked a position fix. I heard Denise again from above in a sing-song tone, “Halfway through my watch, who’s up next better get tuned up.” She enjoyed being on the helm—but not as much as being off the helm.

“Hey Denise, not time yet for beddy bye, so how about you calm your personal wind and shout me down your weather conditions.” I was teasing.

“Wind steady at 10 knots from nor ‘east. Stars went to bed like I will very soon.” She was playful. “It’s solid clouds. Skip, seriously pitch black like Halloween night, Captain, sir.” —Added for effect.

Fifteen minutes later all was quiet. Denise reported, “I hear something—something strange, I think with our engine.”

She glanced the controls. The engine wasn’t running.

“What the heck?”

There was that moment we all fear.

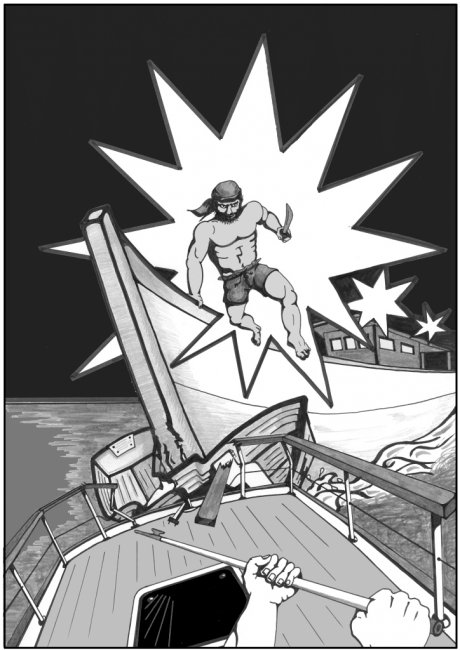

Bathed suddenly in light from the aft port quarter Denise turned, squinting into the brilliance of a large commercial fishing boat rapidly bearing down on us.

Her blood ran cold.

Two fierce looking men stood beside the cabin, pistols in hand. A third, brandishing a grappling hook was in the bow. The light was blinding. There was no mistake. It was coming for us.

“Skip, Come quick! Skip! Skip! A big boat—he’s going to hit us! HURRY! GET UP HERE! OOOH SHIT!”

Her scream was pure terror.